Move Beyond Routine OPA90 Compliance

Prepare Response Plans, Develop Best Practices, and Institute Training to Minimize Risks

By John K. Carroll III, Witt O'Brien's

In my consulting role with Witt O’Brien’s, I assist companies in developing pre-plans (response, incident, and emergency) related to compliance. These pre-plans can focus on a particular regulation, system failure, contagion outbreak, or a natural disaster. With that said, and in light of recent national events, the focus of this article will be on what is commonly referred to as Tactical Plans, pertaining to the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA90) regulations for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), U.S. Coast Guard (USCG), the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Pipeline and Hazardous Material Safety Administration (PHMSA), and Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE).

The five questions listed below are for your consideration. While reading them, think about them in relation to the past several years and you will likely take note of the tremendous changes in many aspects of the industry.

- Do you have the same workforce you did last year?

- Do you have the same consultants supporting you?

- Do you have the same amount of money in your budget to manage your programs?

- Do you have the same policies and procedures as you did last year?

- When is the last time you honestly reviewed your plans top-down?

What is Required?

What is required, and what should be completed are two different things. First, let’s summarize what each agency states with regards to “pre-planning” or “Tactical Plans” under their portion of OPA90.

EPA – 40 CFR Part §112.20 - Facility response plans

A summary of what the EPA requires of regulated operators to develop is as follows:

- An Emergency Response Action Plan, which serves as both a planning and action document;

- Facility information including its name, type, location, owner, and operator information;

- Emergency notification, equipment, personnel, and evacuation information;

- Identification of potential spill hazards and analysis of previous spills;

- Discussion of the small, medium, and worst-case discharge scenarios and response actions;

- Description of discharge detection procedures and equipment;

- Detailed implementation plan for spill response, containment, and disposal;

- Description and records of self-inspections, drills, and exercises, and response training;

- Diagrams of the facility site plan, drainage, and evacuation plan; and

- Security (e.g., fences, lighting, alarms, guards, emergency cut-off valves, and locks).

USCG – 33 CFR Part §154 - Subpart F—Response Plans for Oil Facilities

Under §154.1035 - Specific requirements for facilities that could reasonably be expected to cause significant and substantial harm to the environment, the USCG goes into detail on the types of minimum pre-planning scenarios they require to be developed along with the required pre-planning considerations: staging areas, environmental impacts, personnel considerations, etc.

PHMSA – 49 CFR Part §194 – Response Plans for Onshore Oil Pipelines

Under §194.107 - General response plan requirements, PHMSA discusses the minimum planning requirements a pipeline operator should develop in advance of a release. Discussions include disposal of waste, compliance with the National Contingency Plan (NCP) and Area Contingency Plans (ACP), resource and personnel allocations, environmental considerations, etc.

Under §254.5 General response plan requirements, BSEE states one’s response plan must provide for response to an oil spill from the facility. One must immediately carry out the provisions of the plan whenever there is a release of oil from the facility. One must also carry out the training, equipment testing, and periodic drills described in the plan, and these measures must be sufficient to ensure the safety of the facility and to mitigate or prevent a discharge or a substantial threat of a discharge.

How are Tactical Plans Addressed by Industry?

Some companies accomplish these requirements exceedingly well. However, over my two decades writing such plans, the companies that conduct pre-planning efforts for these programs are often the exception rather than the norm. Most often, companies that comply with the rules, generally speaking, but just that, the agency checklist passed. Remember what the goal of these plans are – they’re not just fulfilling a government requirement – moreover, they are used to prepare for and react to an actual incident.

Too often I see plans that have been photocopied from previous years, maps thrown in with the intent to use as guides, long-winded discussions on how you would respond, or pages and pages on resource capabilities, personnel on-hand, and contractors. Some of this information is worthwhile and does address the requirements of Tactical plans, however, that’s all it really is good for – checking the box. If we step back once we’ve gotten through the rush to get a compliant plan completed and approved, we must ask ourselves, “Can we really use this document in an actual incident?”. The answer often is a resounding “no”.

What is the Correct Approach?

While I don’t have a crystal ball and I realize the information below is necessarily not all-inclusive, it will allow you to get on track in the correct direction.

To begin, you should first know the extent of the pre-planning area, or areas if you’re talking about pipelines. To do this, there are two common methods used – one for spills based on land and water trajectories, while the second method is used purely for water trajectories. When land and water, typically you will use the EPA’s Chezy-Manning formula, details of which can be found in this EPA rule. If purely water, typically you would use the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Automated Data Inquiry for Oil Spills (ADIOS) tool. These methodologies will give you a pretty realistic planning area based on defined parameters.

Once your spill trajectory area has been determined, review the items below:

- Current Environmental Sensitivity Maps (ESMs) and/or other publicly available documents for known areas of concern,

- Current satellite imagery, Google Earth, to determine protection areas, review/confirm surrounding areas, and formulate tactics,

- Applicable ACPs, and

- NCP

With this data in hand, it’s now time to start developing your pre-plans, from this point forward referred to as Tactical Plans. Most in the industry generally consolidate this information onto 11x17 pages, so they are quick guides that can be grabbed in a rush and easily interpreted by responders.

What Data Points Should One Consider?

- Facility Name/Pipeline Name

- Image Description/Name

- Water Body

- Plan Name

- Segment Description

- Response Objectives

- Safety Notes

- Environmental Sensitivities

- Oil Spill Removal Organization (OSRO)

- Equipment/Personnel

- Description

- Quantity

- Decontamination

- Tactical Considerations

- Location Type

- Potential Source

- Collection Point

- Water Intake

- Marina

- Dock

- Boat Ramp (Trailer)

- Boat Launch (Hand)

- Physical Address

- Phone Number/Radio Freq.

- Lat./Long.

- Other Location Information

- Directions

Again, there is no wrong or right way to accomplish these plans, however, in today’s world, organizations can’t afford the risk of not responding quickly and effectively. You must have an understanding of your Area of Responsibility (AOR) to quickly respond, protect, maintain safety, as well as clean up the affected area. Developing these Tactical Plans in advance with profound thought and consideration put into them will serve to add another tool in your organization’s emergency response toolbox.

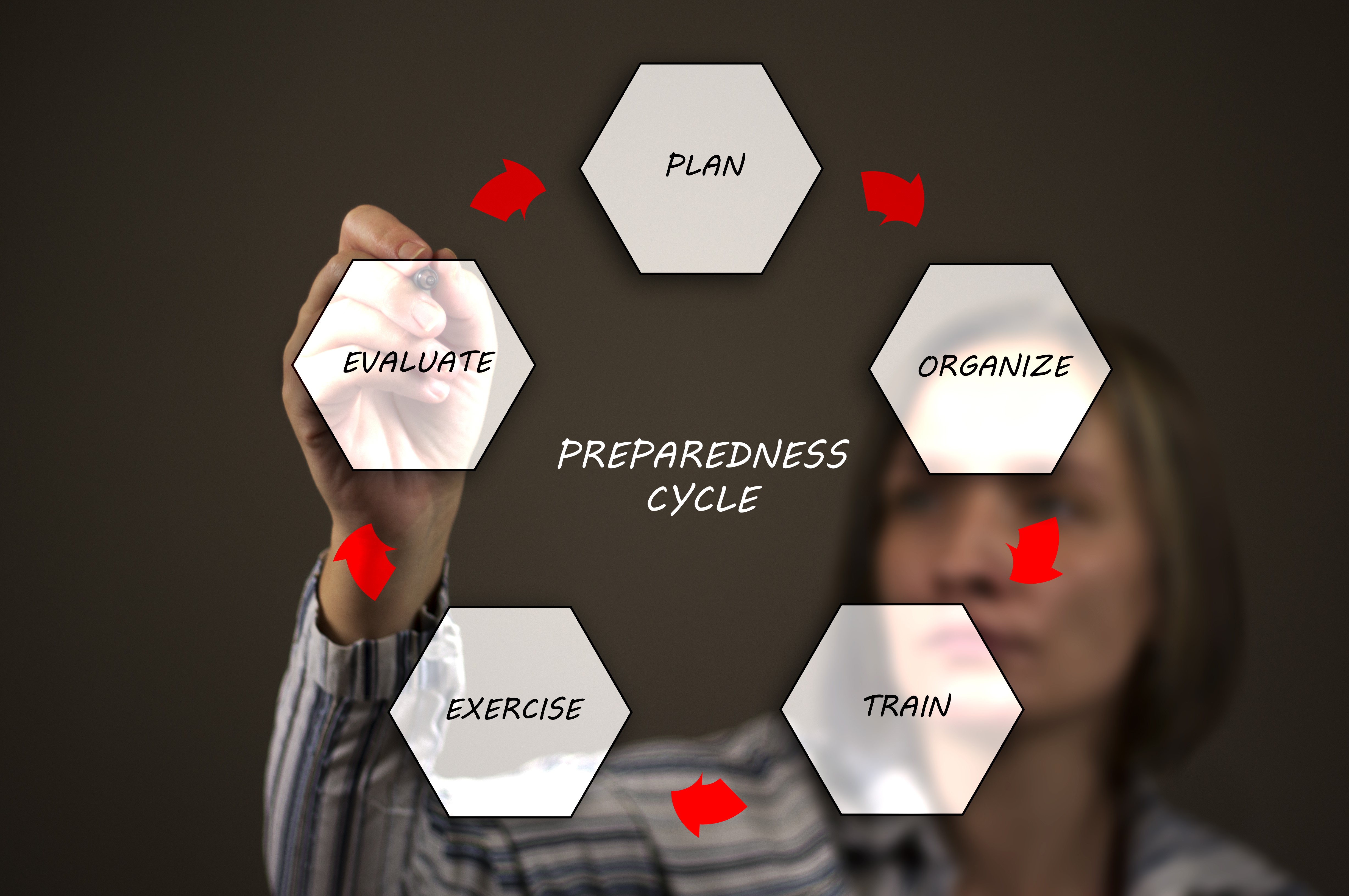

The last step to developing any form of an incident management plan is to train your staff regularly. One of the most important concepts to remember is to train as if it were a real incident. When chaos ensues, which typically is the case during a major incident, it is muscle memory that will serve your company and its staff best. Building this muscle memory isn’t done overnight, so companies need to train regularly.

At a Minimum Training Should Consist of:

- Review of existing plans;

- Collaboration with external resources (private/public) – it’s much easier to respond during an incident when you have a personal relationship with them;

- Ensure personnel has the proper regulatory training for their roles, e.g., HAZWOPER, Incident Management System (ICS), applicable industry-related training;

- Realistic functional exercise that changes from year to year to keep skillsets honed; and

- After-action reviews – best to find out what doesn’t work during peacetime rather when the media and government are at your front door.

John Carroll

John Carroll

Associate Managing Director-Compliance Services

Witt O'Brien

jcarroll@wittobriens.com