U.S. Blockade Has Left Venezuela Shadow Fleet in Limbo

- At least three Venezuela shadow fleet ships have already pivoted to Iran or Russia trades

- U.S. action against Venezuela has sparked a rash of tanker U-turns and satellite spoofing, but many have stopped awaiting orders

- China continues to accept Venezuelan crude from tankers already on the water

Lloyd’s List analysis of Venezuela shadow fleet sees some ships re-routing, some starting to spoof location and several undeterred by the U.S. blockade, but many wait in limbo.

The shadow fleet serving Venezuela’s sanctioned oil exports has been thrown into disarray following the U.S. blockade and the capture of Nicolás Maduro, with vessels scattered across the globe in various states of limbo — some waiting, some rerouting and others disappearing from tracking systems altogether.

A Lloyd’s List analysis of approximately 50 tankers that were laden with Venezuelan oil or enroute to lift cargo as the U.S. imposed a maritime blockade reveals a fleet caught between conflicting pressures: the tightening U.S. enforcement campaign and persistent Chinese demand for discounted crude.

Vessel-tracking data, of those that are traceable via AIS (there are certainly others whose location and status is unknown) from Lloyd’s List Intelligence paints a picture of uncertainty.

Of the vessels tracked that were inbound to Venezuela when the crisis erupted in mid-December, at least six are now drifting or waiting at sea, their operators apparently unsure whether to proceed.

Seven others have pivoted to find alternative employment, with at least two redirecting to service Iranian or Russian oil trades instead.

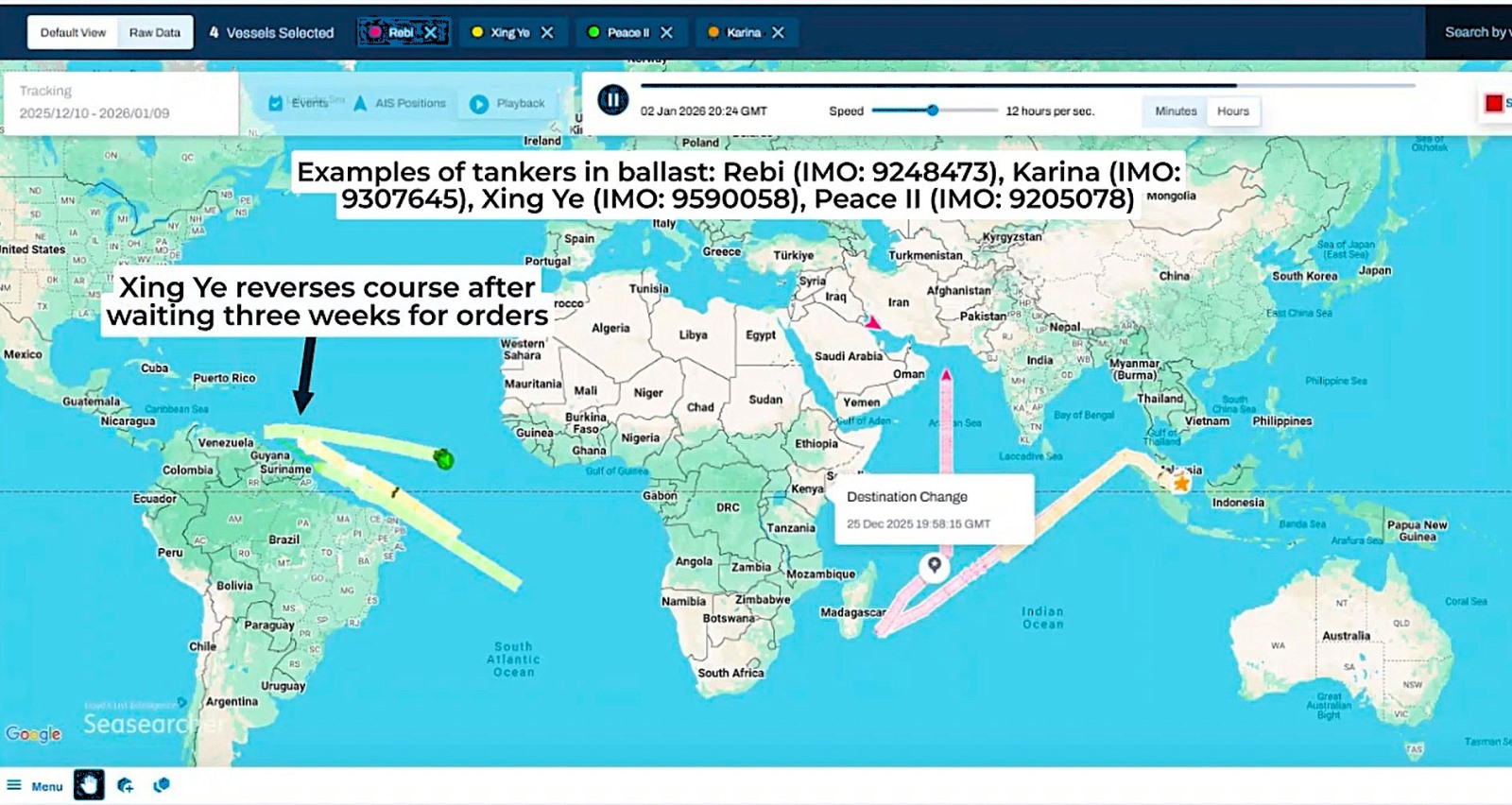

The aframax Rebi (IMO: 9248473) offers a clear example of fleet redeployment.

The sanctioned tanker executed a U-turn while heading toward Venezuela and sailed directly for the Middle East Gulf, where it has now arrived.

The ship started manipulating its Automatic Identification System data shortly thereafter. It is common for tankers lifting Iranian crude to spoof their positional information to show them operating in the Gulf or off Iraq while they load sanctioned barrels.

Another vessel, the Karina (IMO: 9307645), similarly abandoned its Venezuela-bound voyage, making its way to Malaysia’s offshore anchorage where it began spoofing its position — likely pivoting to support Russian or Iranian oil transhipment operations.

Meanwhile, Xing Ye (IMO: 9590058) offers a glimpse of the indecision gripping the fleet.

The VLCC was heading toward Venezuela in ballast when it began drifting on December 19, waiting for nearly three weeks before reversing course on January 8.

Satellite imagery from January 5 confirmed the vessel’s position and that the AIS data had not been falsified.

Xing Ye appears to have abandoned its voyage for the time being, but has yet to pursue a new port of call.

It is one of six tankers that appear to be waiting for orders.

The situation is equally fragmented for those already laden with Venezuelan crude and heading for delivery.

While 11 tankers appear to be continuing their voyages east toward China at normal speed, there are seven vessels that are either paused off the Chinese coast, waiting to berth, or waiting in Malaysian waters.

The VLCC Tina 5 (IMO: 9237761), laden with Venezuelan crude loaded before the crisis, arrived near Zhoushan on December 20 and has remained at anchor ever since, waiting for nearly three weeks with no indication of when it might discharge.

It is not clear if it is the situation on the ground that is causing the delays to unloading operations, though other deliveries in the months prior faced similar waiting times.

Three others have executed apparent U-turns. Seasilk (IMO: 9315147) reversed course in the South China Sea and retreated to Malaysia’s offshore anchorage after initially signaling Yantai as its destination.

White Crane (IMO: 9323429), another laden tanker, appeared poised to deliver its cargo when it executed the beginnings of a U-turn on December 11 after it was designated by the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control. It remained anchored in open waters between Vietnam and the Riau Islands. At the end of December, it sailed into Malaysia waters, where it has lingered since. Its Venezuelan crude is apparently still onboard.

It is difficult to be certain that White Crane’s voyage was not falsified during the period it was at anchor. However, the vessel changed its destination from Dalian, China, to “for order” and its draught information has yet to be updated.

These are both manual inputs, and only further data to contextualize White Crane’s movements will confirm if the U-turn is genuine.

Meanwhile Tamia (IMO: 9315642) appears to be back on course after a series of back-and-forth maneuvers.

The tanker was sailing east towards the Cape of Good Hope when it abruptly reversed course on December 12, the day after being targeted under the same sanctions package as White Crane.

It sailed for the Gulf of Guinea, where it sat at anchor for several days at the start of January before resuming its voyage.

The mid-voyage reversals have raised questions about whether U.S. enforcement actions are deterring Chinese importers from accepting Venezuelan crude. But market sources suggest the picture is more nuanced.

A trader at a key Chinese private refiner told Lloyd’s List that buyers have no concerns about accepting cargoes already on the water. “Vessels can still dock at Chinese ports without problems,” he said.

If Venezuelan supplies were to be cut off in the future, the trader added, teapot refineries would look first to Russian and Iranian crude as alternatives — attracted by comparable discounts and familiar supply chain arrangements.

Yet the physical movement of oil tells only part of the story.

An industry expert offered an alternative explanation for the mid-voyage disruptions: a pricing standoff between traders and Chinese teapot refineries, the ultimate buyers of most Venezuelan crude.

The sudden escalation in Venezuela has driven a wedge between the two sides, the trader said. Traders, anticipating that reduced supply will push prices higher, are seeking to renegotiate terms upward.

Teapot refineries, meanwhile, are well stocked and see no urgency to pay a premium — preferring instead to wait and see how events unfold.

“Some deliveries may have been cancelled, with traders opting to hold inventory for now,” the source said.

Adding to the confusion is the Trump administration’s announcement that it intends to seize 30m-50m barrels of sanctioned Venezuelan crude and release it onto the global market. But the lack of detail has left market participants guessing.

Key questions remain unanswered: how long will it take to restart exports under Washington’s control? How much of the oil will be absorbed by the U.S. domestically? And crucially, will sales to China be permitted, and at what price?

“Prices for Venezuelan crude in China have been rising every day since Maduro’s capture, but there have been very few actual transactions,” the industry source said. “This shows that buyers and sellers are still in a standoff.”

Despite the disruptions, some vessels have continued their voyages without apparent hindrance. At least five tankers completed deliveries to China post-crisis with their AIS operating normally — suggesting that for some, the enforcement pressure has yet to bite.

Yong Le (IMO: 9623257) is currently discharging its cargo in China, while Alma (IMO: 9321304) delivered between December 17 and 20; both cargoes loaded before the crisis escalated.

Several vessels have resorted to deceptive shipping practices to obscure their movements.

At least six laden tankers are employing AIS spoofing or have disabled their transponders entirely to disguise their deliveries to the end buyer.

It is not uncommon for tankers that engage in this trade to operate on the shadowy side of things, but it is a notable shift for the tankers that previously transmitted openly during the final leg of their journeys, which suggests heightened caution amid the enforcement crackdown.

About the Author

Mark Sa

Lloyd's List Intelligence

Mark.Sa@lloydslistintelligence.com